Photo source: www.blog.camera.org, www.teachersreflect.wordpress.com

“Whoever

loves discipline loves knowledge, but whoever hates correction is stupid”.

Proverbs 12:1

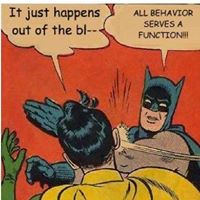

As a BCBA,

you will often find yourself in the position of having to say or do something

intended to change behavior.

I’m not talking about the behavior of your

clients. I mean the behavior of your colleagues, subordinates, or the consumers

who solicit your services. In plain talk, this could mean your supervisees, the

parents of a child you work with, a teacher at the school where you consult,

your employer, etc.

There really

is no exemption from this one. If you plan to step into a

supervisory/management role, part of that role means having to correct others

at times. For some of us, this is an extremely dreaded role. Most people would

LOVE to just ignore these kinds of issues and hope they get better on their

own. It’s just easier that way, right? Shouldn’t confrontation be avoided at

all costs?

Oh my

goodness, NO.

Whether you’re

the BCBA, you work under a BCBA, or you must work with a BCBA, hopefully this post will help you learn to receive or

give appropriate correction.

Firstly, I

have to share my own experiences with this. As a new supervisor, I used to hate

giving correction. I avoided it if at all possible. It made me uncomfortable to

deliver it, and it typically was not well received anyway, so it just seemed

like a lose-lose situation.

Then I

started to overcompensate by freely giving criticism, not correction. (If

you aren’t sure of the difference, just keep reading)

I’m not sure which is worse…...the supervisor

who never gives you any feedback, or the one with standards you can never meet.

Both will quickly lead to dissatisfied consumers, and severely unhappy staff.

Finally,

I evolved to my current view on correction. Mainly, that it is my

responsibility as the leader of the team to not just encourage/support, but

when necessary to correct/rebuke. If I am teaching a child to stack blocks,

what would happen if I never corrected an incorrect response? How could they

learn a skill if I never gave any feedback when they made an error? That doesn’t

make much sense. Well, it also doesn’t make sense to think that your staff or

the consumers you serve can learn to implement a treatment plan if they never

receive correction when they miss the mark.

A

good tip to know if you are correcting or criticizing is to check

your intent. Correction has the intention of making someone better. It implies

that you care about this person, and whether or not they succeed. Correction is

done privately, politely, and objectively. Correction should not include

personal attacks or offensive language, and should include both speaking and listening to what the other person

has to say.

I

have worked with quite a few staff who tended to react extremely badly to

correction. I always left supervision sessions with them feeling like I had

done something wrong, or needed to go easier on them. Then I realized that

there are those who can receive correction, and those who cannot. If ANY kind

of correction or assistance given to your staff is met with defiance, a bad attitude, or defending themselves, then let me break the

news: You are dealing with someone who

hasn’t learned how to receive correction.

Here

are my guidelines for delivering effective correction that respects the

receiver:

- Praise publicly, correct privately – Especially when working with new staff, I like to “catch ‘em being good” the same way I do with my clients! Particularly in front of the child’s parents, I strive to acknowledge what the staff does well, or what their strengths are. It’s just the opposite if you need to correct something. This should be done 1:1 (away from the client of possible), in a low tone of voice, more a personal conversation than a public broadcast. Just say NO to the mass emails where you CC the entire therapy team to call out 1 therapist (I hate when supervisors do that).

- Be direct and open – Beating around the bush or prolonging the inevitable just makes people feel irritated and uncomfortable around you. If you need to discuss inappropriate work behavior with a staff person, just do it. Don’t keep dropping little comments or hints, just say what you mean. People respect someone who can be straight forward and honest. …and definitely do not talk about the issue with others, and not directly with the person. That will completely kill your credibility, and make YOU look like the unprofessional one.

- Seek to understand more than you seek to be understood – When I am having difficulty getting staff or a parent to correctly follow my treatment plan, I first try to find out why. I ask them do they have questions about it, is there something we should change, is some part ineffective, etc. What I am trying to find out, is what is the barrier. I want to understand the problem, so I can help us get over it.

- Don’t get sucked into a debate – When people feel attacked they go on the defense. So you want to be prepared for that, and (more importantly) you don’t want to encourage it. So if the staff starts listing all these complaints about you, or the company, or telling you how hard their life is, or blaming you for their error, you have to keep your composure. You can’t help this individual if you get angry and start attacking them back. Calmly and clearly state what the person needs to correct, explain how they need to correct it, and then ask for questions/further clarification.